UNMASKED

UNMASKED

Throughout the Syrian conflict, victims, witnesses, journalists and United Nations investigators revealed horrifying acts of cruelty, carried out by groups of armed men. Killings. Arbitrary detention. Torture. Sexual violence against men, women, boys, and girls. There appeared to be no crime these groups would abstain from committing.

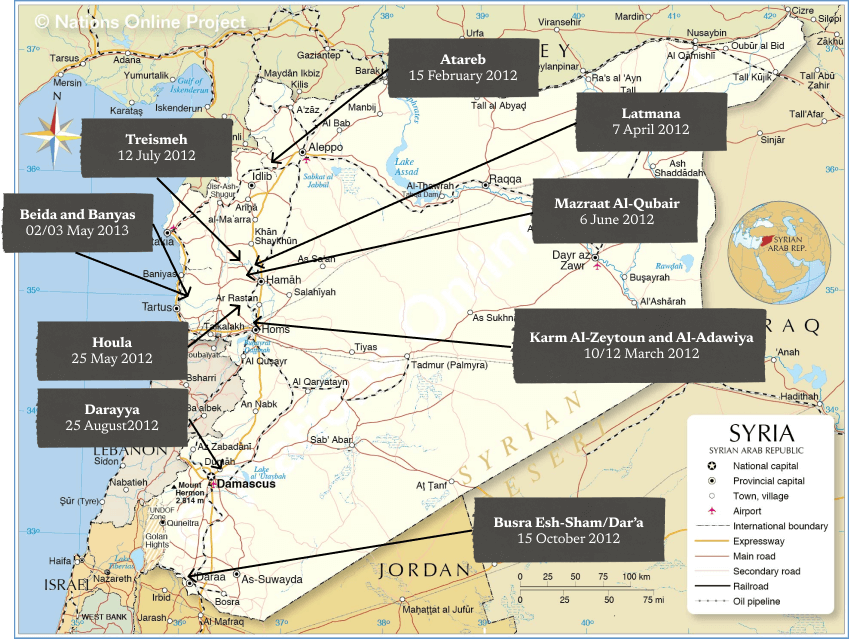

As early as August 2012 an investigation by the UN Commission of Inquiry (COI) into a series of attacks by these armed groups found that they formed part of a pattern of unlawful killings and other crimes committed in anti-Regime areas across the country. Attacks occurred in concert with the Syrian armed forces, who would begin with blockades and shelling before ground assaults of special forces and armed Shabbiha gangs. Searches would be made house to house, removing and executing activists, defectors, fighting aged men, and often, their family members or other randomly selected individuals. Before long, the news of unprecedented massacres of civilians by the secretive pro-Regime paramilitary groups flooded the international media.

Throughout the Syrian conflict, victims, witnesses, journalists and the United Nations investigators revealed horrifying acts of cruelty, carried out by groups of armed men. Killings. Arbitrary detention. Torture. Sexual violence against men, women, boys and girls. There appeared to be no crime these groups would abstain from committing.

As early as August 2012 an investigation by the UN Commission of Inquiry (COI) into a series of attacks by these armed groups found that they formed part of a pattern of unlawful killings and other crimes committed in anti-Regime areas across the country. Attacks occurred in concert with the Syrian armed forces, who would begin with blockades and shelling before ground assaults of special forces and armed Shabbiha gangs. Searches would be made house to house, removing and executing activists, defectors, fighting aged men, and often, their family members or other randomly selected individuals. Before long, the news of unprecedented massacres of civilians by the secretive pro-Regime paramilitary groups flooded the international media.

The reports drew upon circumstantial evidence which showed that the Shabbiha The term “Shabbiha” has generated its own momentum in the Syrian conflict, but it does not always assist in understanding the context, nuance, variety or development of key defined Regime loyalist or parmilitary groups nor their link to the formal security structure. The term can mask a number of recognised pro-Regime groups, including mobilised pro-Regime loyalists, Ba'athist supporters, village defence forces, tribal groups, Popular Committees and other paramilitary groups. Moreover it is not a phrase routinely used by the Syrian authorities in their own documentation. acted alongside Government forces, forming part of the Regime's response to the protesters and opposition. But there appeared to be no direct evidence of this relationship. The COI Report considered that "Eyewitnesses consistently identified the Shabbiha as perpetrators of many of the crimes described in the present report. Although the nature, composition, hierarchy and structure of this group remains opaque, credible information led to the conclusion that Shabbiha members acted with the acquiescence of, in concert with or at the behest of Government forces."

In the years that followed, more information on these paramilitary groups, their crimes and membership was revealed. The crimes themselves were in the main well documented through social media, videos, as well as witness, survivor and defector testimonies. Similarly well reported was the localised set up, membership and patronage of these groups. But no undeniable link to the Syrian State apparatus could be established.

Autocratic states have historically utilised paramilitary groups to do their dirty work in order to claim plausible deniability. Whereas the link and benefit to the state could be perceived, it was difficult to prove in the court of law. The Syrian Regime was no different, appearing to resort to outsourcing some of the most vicious acts of violence of the conflict.

CIJA can now reveal how the highest levels of the Syrian Regime planned, organised, instigated and deployed these paramilitary groups in order to assist the state's crackdown on the opposition. Among CIJA's collection of over one million pages of documents produced by various Syrian state entities are those detailing the growth of the paramilitary organisations from small -or neighbourhood- level loyalist groups to a well-organised militia.

Although the Syrian Regime predominantly deployed its formal security structures to suppress anti-Regime demonstrations, it also featured the mobilisation and use of pro-Regime loyalist or paramilitary groups. Evidence in CIJA's possession -documents issued, signed and stamped by members of the Syrian Regime- show how the highest levels of the Regime mobilised, coordinated and supervised a wide cohort of Assad loyalists including Ba'ath party members, village defence forces and tribal groups, formalising some into Popular Committees and, ultimately, the National Defence Force.

Pro-Regime loyalist groups were mobilised and used from the very early stages of the conflict, which was characterised by the outbreak of unprecedented demonstrations and the appearance of anti-government, anti-Assad graffiti in some areas of Syria.

Following protests in Aleppo on 17 January 2011, instructions were circulated through the branches of the Regime's security agencies and down to local Security Committees to utilise Ba'ath party resources and infrastructure -amongst others- for these purposes. The Security Committees operated in every governorate, coordinating the work of the security agencies and, until November 2011, were headed by the Ba'ath party leader of the respective governorate.

In Deir ez-Zour, 400 kilometres away, the Head of Military Intelligence Branch 243 sent the order down the chain of command requesting Branch sections and detachments to remain alert, plant informers, operate patrols, and prevent the occurrence of further protests by taking any “necessary actions”. The circular ended by demanding full compliance and insisted that “no leniency” would be given in implementing this instruction.

A few weeks later, the same intelligence head chastised their subordinate units for failing to supress “abusive graffiti” and instructed them to crack down on it by streamlining the work of security forces and loyalist groups, including Ba'ath party apparatus and members. These were not isolated instructions stemming from regional or local authorities.

The documents refer to instructions issued by the National Security Bureau (NSB), a long-standing state security body responsible for coordinating all security agencies of the Syrian State. Up until late March 2011, the NSB passed instructions through to the security bodies for action, after which it distributed and oversaw the implementation of instructions and decisions issued by orders of the newly established Central Crisis Management Cell. The decision to engage the loyalist groups to assist in suppressing the protests came from the highest echelons of power.

By 02 March 2011, the breadth of loyalist groups directed to respond to the situation was increased with an instruction issued by Military Intelligence to “mobilise and activate the work of all security agents, informers, sources and Ba'ath Party sub-divisions, popular organisations, leaders of National Progressive Front parties and all friends” who were tasked to detect graffiti, publications or gatherings within their area and to report them immediately. Six days later, the same Branch received a more acute instruction to “intensify monitoring and streamlining the work of sources, informers and members of the Ba'ath Party.”

However, the suppression was failing, with demonstrations and opposition activity spreading across the country, bringing in larger numbers of people with each passing week. On 16 March 2011 thousands of people protested on the streets of Damascus, Aleppo, Deir ez-Zor, Hama and Dar'a. Colloquially known as the Day of Rage, this marked the beginning of the nationwide uprising against the Regime.

The most convenient and effective structures to draw upon in search of loyalists was the Ba'ath Party: its extensive web of branches, divisions and sub-divisions stood ready to be taken advantage of.

Between March and April 2011, the Regime used this network to establish new organisations with local knowledge and networks to confront the opposition: the Popular Committees. Membership consisted of Ba'ath party loyalists as well as trade unions, which fed the Regime narrative of an organic, popular, pro-Regime response to the demonstrations, rather than merely an Alawite faction. Documents in CIJA's collection show how these Popular Committees were anything but spontaneous, but were instead a closely instructed and monitored state organisation, under the instruction and tutelage of the local Security Committees, agencies and police.

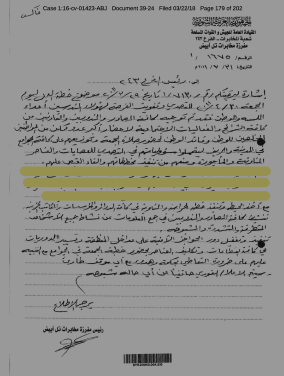

A snapshot of how this worked can be found in communications from Raqqa Governorate.

On 30 March 2011, instructions were issued to all sections and detachments, including to the Chief of Detachment in Tell Abiad, with the Head of Military Intelligence Branch 243 in Deir-ez-Zor (over 200 kilometres away) instructing the Detachment to “draw up an action plan” to confront the opposition with full and effective coordination and instant communication, along with the creation of two groups of Ba'ath party members: one to be deployed in mosques and the other as “a reserve force that waits at offices”.

The Detachment Chief quickly requested clarification on the order, receiving further instructions the same day:

On 7 April the Security Committee of Tell Abiad district held a meeting and among other matters issued “an instruction to Ba'athist comrades to show up for prayers and mosques on 8 April 2011”.

Shortly afterwards the use of Ba'athist loyalists was further formalised within the overall security measures implemented by the Regime. On 11 April 2011, Military Intelligence Branch 243 sent out a request to its sections and detachments and instructed them to:

Such documents confirm that the Popular Committees were integrated within the Ba'ath party chain of command and demonstrate how they were rapidly integrated into the Regime's overall security coordination efforts.

In fact, documents in CIJA's possession show how while these actions were taking place on governorate level, they were overseen and orchestrated from the highest echelons of power in Damascus.

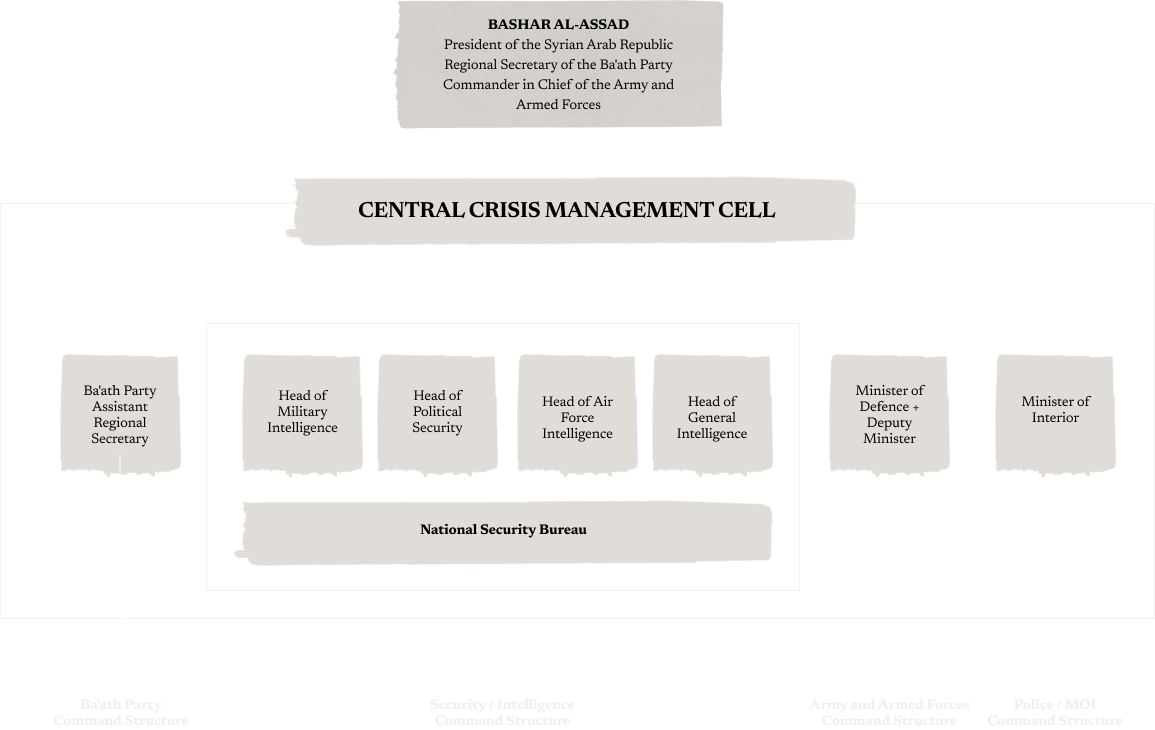

As the Regime continued to lose its grip on the situation, protests escalated into armed opposition, and the authorities took steps to improve and centralise control of its security response. The existing model of communication, information sharing and coordination between military, political and security elements was considered to be insufficient. The Central Crisis Management Committee (CCMC) -an ad hoc senior level committee- was created in March 2011 to coordinate the Regime's response to the uprising. The senior decision-making body reported directly to President Assad and brought together the senior heads of the national security and intelligence agencies, the Interior Minister, the Defence Minister and others into a single leadership body.

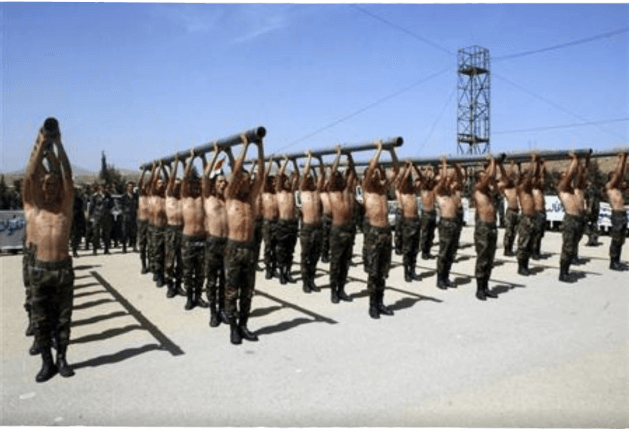

In one of its first instructions on 18 April 2011, the CCMC declared that the “time of tolerance and meeting demands is over” and that a “multi-faceted confrontation of demonstrators, saboteurs of security and vandals” was to be undertaken. The Popular Committees and other groups were ordered to undergo military and security training on the use of weapons and in confronting opposition demonstrators and they were ordered to counter opposition demonstrations, as well as apprehend and hand over suspected opposition members to the security and army, marking an escalation from their earlier role in guarding buildings to directly and forcibly targeting opposition members. Moreover, the Regime sought to maintain oversight and control of these groups by ordering the placement of trained personnel into these units to ensure that their actions were well organised.

Yet more documents show how this order was acted upon. A CCMC report dated 11 May 2011 included a report of a high-level visit to Homs, which demonstrated that leadership of the CCMC met directly with loyalist groups to implement the order and roll-out their members across the city. Ba'athist governorate leadership were instructed to assist in dealing with the opposition, with the city to be divided into zones or sectors (often referred to as departments), each supervised by a leading member of the security branch. A few days later, the Ba'ath Party in Idleb requested and received approval from the Head of Branch 271 to train 100 'citizens' while numerous documents between Branch 271, the Security Committee and the Ba'ath Party Branch reveal requests and approval for the supply of Russian rifles to arm named civilians.

As the conflict escalated over the summer, the role of Popular Committees and other pro-Regime groups in suppressing the opposition was further integrated with the military and security forces. On 5 August 2011, the CCMC met to discuss poor communications between the formal security apparatus and various loyalist groups resulting in “human and material losses” and allowing “armed gangs to keep conducting acts of looting plunder killing and intimidating citizens.”

The CCMC discussed how to better synchronise the work of the security agencies. The following day, the NSB passed down CCMC instructions to governorate-level Secretaries of the Ba'ath Party, i.e. the Heads of Governorate Security Committees. Daily joint military/security operations were to be conducted to arrest individuals from specific groups and to set up Joint Investigative Committees to process detainees. The Popular Committees were to be used to maintain control of areas “cleansed” of the protesters.

These instructions were passed down through the chain of command to the Secretaries of Ba'ath Party branches in the Hama, Deir-ez-Zor, rural Damascus, Homs, Idleb and Dar'a governorates, who in turn instructed their subordinate units to carry out the order. Before long, documents show that instructions were given for these groups “to be trained to use weapons in coordination with security agencies”.

The allocation of such clearly defined roles to pro-Regime paramilitary groups in controlling territory is critical to understanding why such groups were noted as being present during or after operations undertaken by the Syrian security forces.

Throughout 2011 and 2012 witnesses and survivors consistently reported the presence of “Shabbiha” -as they called them- at various massacres across the country.

The crimes committed by the paramilitaries were undeniably reported up the chain of command. However, to no avail.

Some early CCMC documents show attempts to abolish the Popular Committees, possibly in reaction to increasing reports of looting and crimes committed by their members. For example, on 20 April 2011 CCMC meeting conclusions were circulated through the Regional Command, including an order “cancelling the Popular Committees.” Four days later, CCMC issued minutes from its meeting on 22 April 2011, where it “confirmed that the Popular Committees will stop working” with responsibility for “keeping order in [the] governorates” lying with the Ba'ath Party and Security Committees.

But these efforts were not genuine attempts to stem the use of irregular forces and militias. CCMC documents issued that same week instructed the continued use of loyalist groups, in addition to arming and training them.

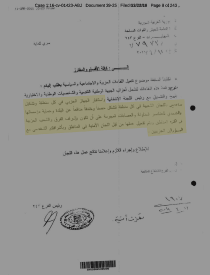

The level of violence and the criminal conduct of the militia was unpalatable even to some representatives of the official security and military apparatus. This led to occasional clashes and arrests of the loyalists. The Regime's highest-level leaders undeniably knew that these groups were carrying out criminal acts.

Yet, as some documents in CIJA's possession show, they instructed their subordinates to let the militias be, rather than investigating or punishing them, in clear breach of their responsibility as superiors or commanders.

For example, Branch 271's instructions show it was aware that the popular organisations had engaged in abuses against the civilian population, including arbitrary arrests, kidnappings, and personal score-settling. A group which was under the patronage of the Air Force Intelligence Branch in Idleb and armed with regular and machine guns, as well as rocket-propelled grenades, gained notoriety for its unlawful detention and mistreatment of citizens.

The instruction from Branch 271 to its subordinates however was clear: “Some of the security branches arrested these comrades. Therefore, please make sure that the security and military checkpoints pay attention and do not oppose them.”

The Regime's increased tolerance and reliance on paramilitaries was driven by the conflict context at the time. The opposition's armed faction -grouped under the umbrella of the Free Syrian Army- had taken large swathes of territory, while sizeable numbers of Syrian soldiers and commanders had defected to the opposition.

One of the Regime's responses was to absorb and integrate the Popular Committees into a formal government paramilitary force called the National Defence Force (NDF). A Syrian Army Commander explained that the NDFs were set up as the leadership had started to lose faith in the army and its effectiveness, and as a lot of soldiers had fled or joined the opposition. By 2013 these new formations were being sent to the battle-front, giving the loyalist militia yet another role in the conflict.

The Regime's increased tolerance and reliance on paramilitaries was driven by the context of where the conflict stood at the time. The opposition's armed faction - grouped under the umbrella Free Syrian Army - had taken large swathes of territory, while sizeable numbers of Syrian soldiers and commanders had defected to the opposition.

One of the Regime's responses was to absorb and integrate the Popular Committees into a formal government paramilitary force called the National Defence Force (NDF). A Syrian Army Commander explained that NDFs were set up as the leadership had started to lose faith in the army and its effectiveness, and a lot of soldiers had fled or joined the opposition. By 2013 these new formations were being sent to the battle front, giving the loyalist militia yet another role in the conflict.

An NDF Commander at the time told the media that his forces brought the civilian militias under a formal military structure with military discipline that provided training and weaponry.

CIJA's collection of documents from Idleb shows that, from 2014 onwards, the NDF forces were under the command of the local Security and Military Committee. Documents show the extent of control and supervision exercised by the Head of the Committee who issued regular instructions to his subordinate forces, including the NDF.

The level of command and control can also be inferred from the fact that the NDF Commander was requesting approval from the Head of the Idleb Security Military Committee for tasks as mundane as requesting other security and military forces to search for a missing assault rifle. Finally, documents show that the Idleb Security and Military Committee also received official reports from General Intelligence on incidents of alleged criminal activity by NDF fighters, indicating that the security agencies had a role in disciplinary control over NDF units.

The NDF represents a culmination of the Regime's embrace of loyalist groups and their transformation into an entity that is intrinsically intertwined with official structures. Transformed from the early eyes and ears of the Regime to brothers in arms with the Syrian military and security forces, the loyalist groups have grown in size and importance since the beginning of the war. While the Regime's initial attempts may have been to publicly deny this connection, the documents collected by CIJA's investigators undeniably reveal the connection between it and the paramilitary groups drawn from the Ba'ath party ranks.